The Blockade of Cuba Does Exist

especiales

It’s virtually impossible to understand the current state of the Cuban economy, as well as its historical development over the past 64 years, without analyzing the profound impact of the economic, financial, and commercial blockade the United States has imposed on Cuba, which Commander-in-Chief Fidel Castro Ruz once described as an economic war that typifies genocide against an entire country.

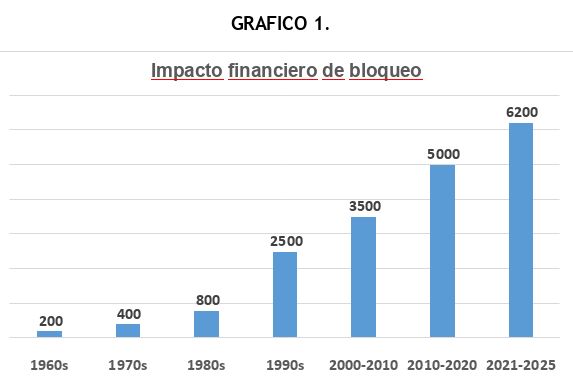

From a chronological perspective, the impact of this aggression, with its social and political effects, shows a sustained increase in the losses inflicted on the Cuban economy, according to the following graph from the 1960s, when this siege began, until now.

As can be seen, the monetary effects increased from an annual average of USD 200 million to USD 6.2 billion by the end of the second decade of the current century. By the end of March 2024, the total amount had reached USD 162.68 billion, according to the latest resolution issued by the UN: "Necessity of ending the economic, commercial, and financial embargo imposed by the United States of America against Cuba" (A/79/L.6).

An essential aspect, which makes the blockade even more illegitimate and cruel, has to do with its clear extraterritorial effect, contrary to the US narrative that this policy is a combination of bilateral sanctions and that Cuba can trade with the rest of the world. Legislation such as the Helms-Burton Act or the Torricelli Act, or especially Cuba's inclusion on the spurious list of countries that sponsor terrorism, give the blockade this extraterritorial meaning, functioning as a kind of global siege, based, first, on the perfected use of sanctions as part of the war on terrorism during the George W. Bush administration, and then on developments made, especially, during the Donald Trump administration. As part of the evolution of the sanctions system, the following have been identified:

- "Secondary sanctions," targeting actors in third countries to discourage them from maintaining trade or financial relations with the entity or state that conflicts with the interests of the United States.

- "Smart sanctions," targeting a country's key sectors (such as tourism and the export of medical services in Cuba, or Venezuelan oil) or critical institutions (such as a central bank). It’s noteworthy that these can have devastating effects on an entire economy and its population, in addition to the multidimensionality of their impacts. For example, an oil embargo could simultaneously weaken the economy and military capabilities of a target country, transmit a military threat to it, and send a message to other countries.

- Shared sanctions regimes, for example, between the European Union and the United States toward Venezuela and Russia.

- The systematic application of the aforementioned sanctioning modalities to allied countries, for example, Cuba and Venezuela.

During Donald Trump's first administration, with clear continuity from Biden, the blockade manifested itself in a series of measures that sought to surgically cut off the country's access to any source of foreign currency. This included sabotaging Cuba's renowned health cooperation, employing pretexts and lies, and blackmailing the governments that receive this cooperation with sanctions against the executives who manage it.

Regarding the use of economic sanctions, Trump promoted the implementation of particularly creative methods to ensure that his administration's measures would cause the greatest possible damage. An example of this was the shift in focus of economic sanctions against Venezuela from officials to key sectors and institutions critical to that country's economy (oil, mining, Central Bank), the 243 measures taken against Cuba focused on the same goal (tourism, export of medical services), and the dimensions outlined in the economic war against China.

The so-called smart sanctions, strengthened within the framework of alliances between governments and the private financial sector, as identified by Zarate (2013) in his definition of financial or Treasury war, were applied simultaneously to allied countries, such as Cuba and Venezuela, eroding the support bases to face the situations that affected each nation, as part of a systemic war against governments of countries classified as authoritarian governments or dictatorships, which includes their application by a coalition of States, strengthening their effect, and making it difficult for the target state to evade them. The aforementioned has been considered an act of war and falls under what has been defined as the securitization of the economy (Vázquez, 2024 and 2025).

Among the conditions for the "adjustment" in the way sanctions are applied, the advice of cabinet members with corporate interests has been mentioned. In this regard, his former Secretary of the Treasury, Steven Mnuchin, a multimillionaire and former Goldman Sachs banker, stood out (https://www.rtve.es/noticias/quien-gobierno-trump/), although the corporate oil sector also had a particular influence on actions toward Venezuela, particularly the actions of Red Tillerson, who had served as CEO of Exxon Mobil Corporation between 2006 -2016. Corporations such as Bacardi, along with the United States-Cuba Political Action Committee for Democracy, led by Mauricio Claver-Carone, promoted the measures against Cuba (Vázquez, 2024).

With the second Trump administration, a group of figures with a long pedigree has clearly gathered around aggressive projects toward Cuba, starting with the current Secretary of State, Marco Rubio, and the White House delegate for Latin America and the Caribbean, Mauricio Claver-Carone, supported by congressmen of Cuban origin, who have made the war against the Cuban people their political rationale and source of financial resources.

Since Trump took office on January 20, 2025, a group of measures have already been approved. Except for the sanctions against executives who manage health cooperation, the rest are virtually a recycling of measures already taken previously.

Briefly, these measures, as of April 9, 2025, are: Re-registration on the List of State Sponsors of Terrorism; activation of Title III of the Helms-Burton Act; reactivation of the Restricted Entities List, travel and entity restrictions; reactivation of the Guantanamo Bay Detention Center; It imposes sanctions on Cuban and third-country entities and executives linked to Cuban medical cooperation, among others.

In all these years of growing hostility, Cuba has accumulated vast experience in dealing with this siege. There’s also a conviction that the US authorities should not be expected to lift the blockade, and that only through our own efforts and international solidarity can it be overcome.

We have a culture of resistance and resilience among the Cuban people, as well as the resolve to move forward. In any case, the Revolution developed extraordinary human capital and the political consensus necessary to face these adverse circumstances and win.

Translated by Amilkal Labañino / CubaSí Translation Staff

Add new comment