Brazil: The Political Impact of Bolsonaro’s House Arrest

especiales

Every move now resembles a calculated chess match. A single misstep can come at a significant political cost, far greater than in the past. What we are witnessing is the acceleration of political time as the defining feature of the current situation.

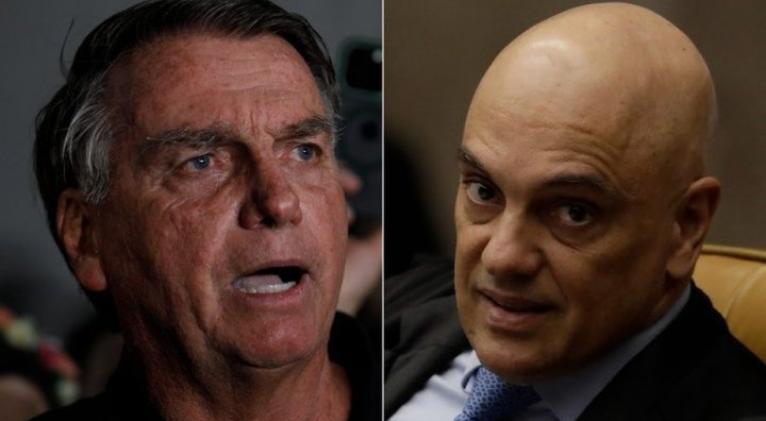

The recent house arrest of Jair Bolsonaro, ordered by Supreme Court Justice Alexandre de Moraes, marks the latest chapter in a political saga involving multiple interests and actors, including the United States government. Within hours of the announcement, the Trump administration came to Bolsonaro’s defense through a post on X (formerly Twitter) by the U.S. State Department’s Bureau of Western Hemisphere Affairs.

At the center of the dispute are pressing economic concerns. Brazil faces potential losses in the billions due to threatened exports, in light of tariffs announced by Donald Trump, adding urgency and gravity to the crisis.

Against Trump and imperialism, the working class must enter the scene with a policy independent of the government and the regime.

Until recently, Bolsonaro remained politically isolated and weakened—a position worsened by the announcement of tariffs and by the prominent role played by his son, Eduardo Bolsonaro, as one of the architects of the economic sanctions.

Major media outlets joined in calls to condemn Bolsonaro’s actions, while key business entities invoked a spirit of national unity and urged President Lula da Silva to act to soften the economic blow of the new U.S. trade barriers.

The emphasis was on negotiation over retaliation, with some advising against applying Brazil’s reciprocity law, which allows the country to impose sanctions on those who sanction it. Lula followed this advice, but his sovereign rhetoric caught the attention of the international press, portraying him as a leader willing to confront Trump.

This earned Lula political capital. Riding a wave of renewed support for Brazil, he managed to recover some of his previously declining approval ratings. Anti-imperialist sentiment, long absent from Brazil’s political mainstream, resurfaced in public discourse.

Meanwhile, the trial over the reactionary events of January 8, 2023—when Bolsonaro supporters stormed the seats of all three branches of government—was progressing, with expectations for a conclusion by the end of the year. In a notable shift toward a more defensive posture, Bolsonaro testified and even joked with Justice Moraes, asking whether he would accept being his vice president. The moment seemed cordial, but the intent was to project harmlessness.

It was precisely this attempted foreign interference that accelerated the pace of events. Once Trump publicly stated that his tariffs were partly aimed at protecting his Brazilian ally, harsher legal measures swiftly followed. First came the electronic ankle monitor, then house arrest for violating precautionary court measures. All of this unfolded while Moraes was himself targeted by U.S. sanctions under the Global Magnitsky Act—a move The Economist described as unprecedented.

Until recently, few questioned Moraes's actions. While occasional concern was voiced, most analysts and editorial boards backed the Supreme Court. That stance has begun to shift in recent days.

With the headline “Moraes’s Gift to Bolsonaro,” Estadão was the first major outlet to argue that the move could backfire. Folha de S.Paulo, in a similar editorial, stated that “Bolsonaro has the right to freedom of expression.” Several commentators suggested that Bolsonaro had intentionally provoked his arrest in order to portray himself as a victim of political persecution, even before being formally convicted.

There is now widespread discussion of whether Moraes’s precautionary measures were “unorthodox.” Banning interviews and even third-party social media posts has been deemed excessively vague and constitutionally problematic—a key issue cited under the Magnitsky Act.

Yet a crucial point is being consistently overlooked: the judiciary’s ambiguity and overreach did not begin with Bolsonaro. Though the current target has changed, it is not difficult to recall how the Supreme Court employed overtly political and authoritarian methods to imprison Lula and support the 2016 institutional coup.

The court not only endorsed the flagrant abuses of Operation Car Wash and Judge Sérgio Moro, but also banned Lula from giving interviews. Even more egregiously, Lula’s imprisonment was a decisive factor in the 2018 election outcome, which ultimately brought Bolsonaro to power—arguably the most severe case of judicial interference in Brazil since redemocratization.

Now locked in a direct confrontation, Bolsonaro and the judiciary are clashing once again. His detention for violating court orders provides an opportunity for the far-right movement to exploit.

More than mere naiveté, it would be shortsighted to ignore the calculated nature of Flávio Bolsonaro’s decision to publish a video of his father online—an act seemingly intended to provoke the judiciary. The speech by far-right congressman Nikolas Ferreira, who helped coordinate the rally, included a call for none other than the arrest of Alexandre de Moraes.

The rally was timed just after Trump’s tariff exemptions were announced, and amid escalating sanctions against Moraes. Those not in attendance also sent a clear message. Tarcísio de Freitas, the governor of São Paulo and Bolsonaro ally, happened to have a surgery scheduled for the same day—a highly convenient absence.

With the imposition of strict precautionary measures, Moraes’s failure to respond could have been interpreted as weakness. However, a more aggressive response risked triggering the very outcome that has now taken place. The judiciary’s own “heterodoxy” has thus been strategically exploited by bolsonarismo.

Still, going too far can result in a misstep—or even a fall. The latter appears unlikely for now. Bolsonaro’s house arrest is not a game-changing event capable of overturning his expected conviction or ending his political isolation. However, it does give his movement valuable rhetorical tools and momentum that could extend beyond the verdict. As groundwork for larger political ambitions, it is not insignificant.

At the same time, Lula stands to benefit from this evolving situation. His government has been strengthened, and in the short to medium term, his firm stance in negotiations with the United States will likely earn him enough support to avoid defections among the business and political elite affected by the new tariffs.

The economic and social consequences of these tariffs remain to be seen, but they will undoubtedly impact all layers of Brazilian society. If the Bolsonaro family is largely blamed for the economic fallout, the judiciary’s role will fade into the background. However, if various sectors come to see the need for a government more aligned with Trump, Bolsonaro and his successors could regain strength and reposition themselves for more ambitious goals.

Placing hope in the judiciary as the primary means of ending bolsonarismo is a precarious gamble. It empowers a branch of government capable of sharp political pivots. Lula’s own arc—from prisoner to president—only underscores how the ruling class will support whoever can bring temporary stability to an otherwise deeply fragmented and crisis-ridden political system.

Allowing Bolsonaro to cast himself as a victim is an insult to the memory of the hundreds of thousands who died during the COVID-19 pandemic, the millions whose rights were violated, and the social movements that resisted Brazil’s descent into authoritarian rhetoric.

The fight against bolsonarismo demands the construction of a political force that is independent from the entire political regime. Concessions to class conciliation only keep the far right within the realm of political viability, fueled by an increasingly aggressive imperialism.

Add new comment